Tchaikovsky: Eugene Onegin (Jansons)

Based on Pushkin’s ‘novel in verse’, Tchaikovsky’s opera is certainly the most popular of his offerings in the genre, and is arguably one of the most personal musical statements from his own very troubled life.

Tatiana is a young, book-learned lady who yearns to find the perfect man, and to marry for love, and not end up in an ‘arranged’ relationship which has been the lot of many of her forbears. Her sister Olga is already engaged to the poet, Lensky, who arrives with a neighbour of his, Onegin.

Tatiana is immediately struck by this handsome young chap and embarks on letting him know all her hopes and dreams, even though she has only learned what she knows about life through books. Onegin is quite taken by the attention, and certainly prefers the thoughtfulness of Tatiana to what he sees as Olga’s superficiality.

Tatiana can’t sleep, and talks to her nurse about love and everything that it entails. Her nurse also had an arranged marriage and tells Tatiana that people never talked about love in her day. It was as if it never existed. Tatiana can’t live like that though, and decides to write a letter to Onegin trying to explain how she feels about him. This takes all night.

Tatiana waits for Onegin’s response, and he pays her a visit to let her know how he feels. It’s not exactly as she would have hoped, as he explains that he doesn’t consider himself suitable for marriage, and although he thanks her for the letter, his advice would be that she should not be so forward to strangers in the future as not everyone is as understanding as him. She is not best pleased by his attitude.

Time passes, and a ball is held in honour of Tatiana’s name day. Lensky has convinced Onegin to appear, but he is a little perturbed by the not-so subtle gossip about him from the other guests. Onegin decides to get some sort of revenge on Lensky by dancing with Olga a few too many times. Lensky is appalled by his behaviour, a feeling which is exacerbated by Olga’s seeming enjoyment from the constant attention from Lensky’s friend. Lensky faces up to Onegin, accusing him of deliberately flirting with his fiancée. Their friendship is dramatically ended by lensky challenging Onegin to a duel.

The following morning, Lensky arrives at the allotted place first and says farewell to Olga and his own life. Onegin arrives late, but the duel still goes ahead. Lensky is killed.

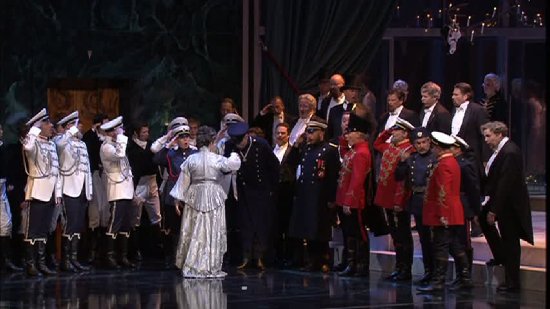

Onegin spends many years abroad after killing his best friend, but eventually returns to St. Petersburg. He attends a ball where he meets a distant relative, Prince Gremin. He also notices someone who looks remarkably like Tatiana, and after enquiring after her to Gremin, discovers it is indeed her, and she is now married to the Prince himself.

He’s not particularly put off by the fact that she is now married, and decides to write her a letter himself requesting a meeting. Tatiana agrees to this, but despite allowing herself to admit that she still loves him, her loyalty is now wholly towards her husband and Onegin is left alone, realising that he has nothing left to live for.

Pushkin’s story is one which would have felt very familiar to Tchaikovsky, as he set it to music at around the same time as he himself was in two minds about getting married, but in his case, to protect himself from the society that would have turned him into an outcast because of his homosexuality. The additional fact that Pushkin himself was killed in a duel (he had taken part in quite a few before his luck ran out) has turned this tale into one of the most famous, almost stereotypical Russian stories.

It would be a brave man who decided that something really drastic needed to be done to make things ‘more relevant’ to modern audiences. In fact, in Stefan Herheim’s case, I’m not even sure that’s what he intends...and to be honest, if he has difficulty in convincing Mariss Jansons, one of the most respected Tchaikovsky conductors, of certain key moments in his production, then you would think he’s on a hiding to nothing.

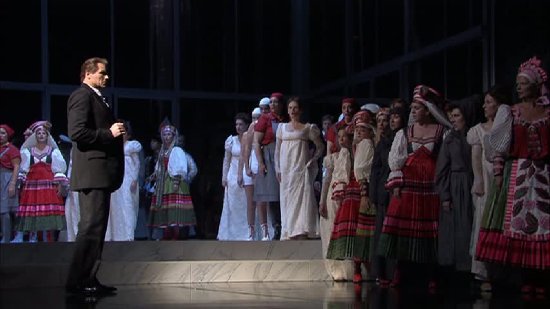

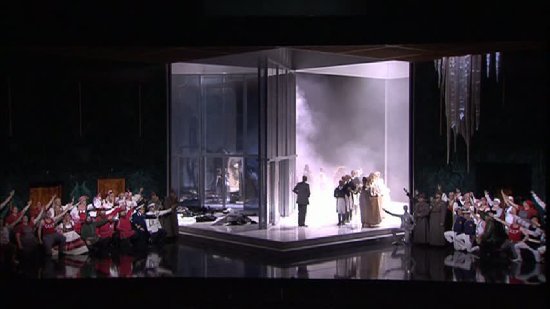

The production begins with the orchestra pretending to tune and the conductor already in place. The cast walk on, and as Onegin joins them, a recording of music from the third act is played. So, Herheim’s ‘triple temporal perspective’ take on the story has already caused this particular viewer some considerable confusion. As the work progresses, further tricks are played, with Onegin seemingly writing Tatiana’s own letter to him, several costume changes reflecting Russia’s vibrant history (in no particular chronological order), alterations to characters’ ages and a whole parade of everything we would associate with Russia in the last act, consisting of dancing bears, cosmonauts, athletes and gymnasts, ballet dancers…..well, I’m sure you get the drift.

It could all easily appear to be a big mess, yet Herheim’s musical knowledge (he’s a cellist in another life) is a big advantage, and he tries hard to convince us that it makes sense to mix the timelines in the way he does as Tchaikovsky uses thematic material throughout the opera that connects different characters at different parts of the story. The idea isn’t too far-fetched and as someone who is familiar with the work, I found it all quite interesting…up to a point. For anyone new to the work however, and there will always be those who are lucky enough to experience it for the first time, Herheim’s staging could appear to be, at the very least, perplexing.

Musically, there is fortunately only one person in charge and Jansons’ expertise in this style means everything moves forward in a fresh and exciting fashion without allowing too much wallowing in what can easily become an exercise in treacle production. The Royal Concertgebouw plays brilliantly and even if there are some slight balance problems, the sound is superb overall with bright and clear orchestral textures.

On stage, despite the awkward scene-meddling, the cast are strong throughout.

Bo Skovhus’s Onegin is a dour, depressive character who’s experience is turned into a long reminiscence of ‘what could have been’, but he is in excellent voice, which is a good thing as much of his time is spent wandering about like a lost soul, silently.

Andrej Dunaev’s Lensky is lighter-voiced than most but his first aria is an absolute belter, and there’s a reasonably believable (if very quick) transformation from Onegin’s friend to arch-enemy, which sees him transform into a revolutionary (one of Herheim’s oddities, time-wise) for a hugely satisfying aria before he dies from an almost nonchalant attempt at a shot from a drunk Onegin (whose second in the duel has become a bottle of Guillot wine, rather than a servant with the same name. Very clever, Stefan).

Tatiana (the excellent Krassimira Stoyanova) is not as young as many have been (Tchaikovsky’s original idea was to use a cast of students), yet unless you have a voice far beyond your years it’s difficult to argue that this isn’t a role for a more experienced singer. The ‘Letter Scene’ is a case in point and you would have trouble finding a more beautifully controlled yet highly passionate account as we see here. Stoyanova’s performance is all the more remarkable when you consider your attention is constantly taken away by Onegin’s completely unnecessary presence on stage.

Age is also an issue in the case of Prince Gremin, supposedly an ageing aristocrat, yet is played here by the relatively young Mikhail Petrenko, thereby turning Tatiana’s sugar daddy into more of a toy boy. His one main aria is sung well however, despite his voice not having the ‘depth’ I like from a Russian bass.

As far as the staging is concerned, you will be disappointed with the lack of grandly-realised Imperial Russian court scenes, especially when it comes to the justly famous dances, but there is enough going on to keep the interest, however confusing much of it is.

The main extra consists of a thirty minute, reasonably sycophantic documentary explaining Herheim’s thought processes into getting this work onto the stage. The overall impression is that he feels his own input is far more important than the work itself, sending us headlong into the Regietheatre world I generally despise. Jansons questions some of the dramaturgical nonsense, yet there doesn’t seem to be any realisation that what may once have appeared a clever idea, could also be seen as a pile of pretentious tosh in the cold light of day.

This is certainly an Onegin worth watching for the performances and it’s a very well-produced DVD, but for anyone new to the work, a more traditional staging is recommended.

Your Opinions and Comments

Be the first to post a comment!