Review for Lowlife Love (Dual Format )

Introduction

They went and did it. Third Window Films only went and made a movie! If you’ve been following Third Window Films the last few years, you might have heard the lament that ‘they don’t make ‘em like the used to’. Japan’s independent film industry is no longer making the quirky, individual and unique cinema that Third Window Films thrives on, the kind of cinema that saw the label come into prominence in the first place. The problem is a global one, that of studios and distributors retrenching, focusing on the sure things, the guaranteed hits, filling multiplexes with comic book movies (or manga movies), and no longer willing to take a chance on originality. That has had the added benefit of Third Window revisiting some veritable classics from Shinya Tsukamoto and Takeshi Kitano in previous years, re-mastering them for their Blu-ray debuts, and keeping the release schedule ticking over. But as for new films, it’s become increasingly necessary for Third Window Films to invest in production, as Japanese independent filmmakers look further afield than traditional sources for financing. Third Window has served as co-producers on films like Land of Hope, and Fuku-chan of Fuku Fuku Flats, but Lowlife Love is the first time that they’ve bankrolled the whole movie.

The blurb for Lowlife Love certainly caught my eye, and in my tendency to make quick connections, I was instantly put in mind of Bowfinger, the US film comedy where a hard-up director blags his way into making a feature film. Then I put that connection out of my mind, not wanting to be prejudicial due to prior expectations. Lowlife Love is a rather dark and satirical look at the Japanese independent film scene, and given that it is an independent movie itself, I certainly hope that it isn’t autobiographical.

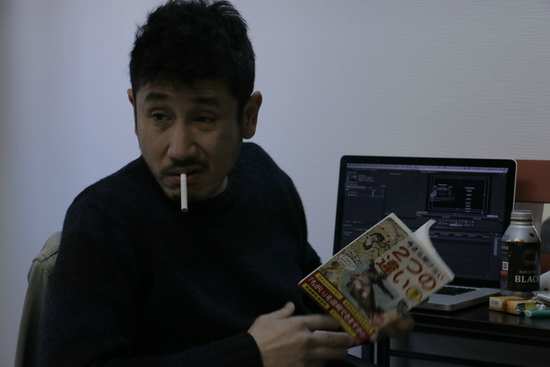

Tetsuo Aoki is a filmmaker. He’s only really made one film that caught the public eye, years ago, and now he lives at home with his mother and sister, runs a dubious actors’ workshop, promising a role in his next big film to his students, he begs, steals, borrows, and scrounges whatever money he can to fund his masterpiece (not that he has one), and he sleeps with as many aspiring actresses as he can. He’s 39 years old, and his last chance to make movies is fading with the years. Then into his life come an aspiring screenwriter, Iori Ken, and a wannabe actress named Minami who enrols in his workshop. Iori has a script, and while Minami is unpolished, Tetsuo can see the talent and the star quality within. This might just be his movie. That’s if he can get away from his lowlife tendencies to exploit and cheat. And even if he could somehow do that, the script and Minami’s talent soon come to the attention of other filmmakers, and it turns out that the rest of the film industry is just as lowlife as Tetsuo.

Picture

Lowlife Love gets a 2.35:1 widescreen 1080p transfer. It’s an unproblematic transfer of a digitally shot film, with very naturalistic, almost documentary production values. The image is clear and sharp where it counts, the colours are consistent, and detail levels are good. Of course things tend to become a little more indistinct in darker scenes, that’s just the nature of the source material. Lowlife Love is a very watchable film, and all the more impressive given that it was shot over just eight days.

The images in this review were kindly supplied by Third Window Films.

Sound

The sole audio track is a DTS-HD MA 2.0 Japanese track with optional English and German subtitles. The dialogue is clear throughout, and the film gets a very apt sardonic music soundtrack, particularly the theme song. But there is a problem with this release, and that is the subtitle font. It’s just too damned small. At my optimal viewing distance, 8 ft for a 37” screen, I was squinting a little too much, and had to skip back once too often to watch a scene again, scooching to the edge of my sofa to get closer. The irony is that the trailer, the extra features all have subtitles appropriately sized to the screen. There’s one typo around 54 minutes in, ‘intention’ spelt as ‘intension’.

Extras

One benefit of producing a film is that you can pick and choose what extras to include, not be beholden to a production committee intent on keeping extras as domestic exclusives.

Insert the disc and you get the choice between English, German, and Japanese animated menus. The extras are the same on all three languages though.

You get the theatrical trailer lasting 2:07.

The Cast Introductions last 11:04, with brief snippets of interview captured on set and on location.

There are three deleted scenes, 8:11 worth, although the first ought to be labelled an alternate scene. There is an extended scene with Kida in the bar lasting 1:58, while the Alternate Ending lasts 1:17.

The Stage Greetings lasts 11:58, where the cast, director and producer get on stage for a little introduction and Q&A. Alas this is one of those pieces where they use the translator’s English translations directly instead of subtitling. It’s not a great microphone in the first place, and he tends to speak under the applause so you’ll miss half of the translations anyway.

The Red Carpet Interviews were captured at the Tokyo International Film Festival and last 5:23.

Behind the Scenes offers 16:44 of b-roll footage and rehearsal footage.

It’s a Wrap lasts 9:04, and captures the actors’ respective last days on the set.

Finally there is a 4:17 music video, scenes from the film set to the theme song.

Conclusion

The Bowfinger comparisons are apt, although this is a dark mirror image of Bowfinger, Bowfinger seen through a cynical, pessimistic and downbeat lens. You get the feeling that the truth about independent filmmaking probably lies somewhere in-between the two. Certainly it’s hard to believe that any movies could get made in the world of Lowlife Love, where money is so scarce that films rarely get off the ground, and the real currency in the industry is sex, where actresses have to sleep with their directors and producers to get cast.

We’re introduced to this world through the eyes of director Tetsuo Aoki, living off the glory of his one film, but now aged 39, still living at home with his mother and sister. He runs an actors’ workshop, and he’ll beg, steal and borrow whatever cash he can, to put forward to his next movie. But you get the feeling that getting that cash has become an end in itself, that his creative days are long past. So it’s as much a surprise to him as it is for anyone else when fate delivers a last chance to him in the form a fledgling screenwriter Iori Ken, and ingénue actress Minami. He has the script that will be his next masterpiece, and she has the talent and the potential to be his star.

In Bowfinger this was the impetus to a madcap tale of blagging, cheating, sneaking, and making a movie on the sly. In Lowlife Love, this is a depressing, more realistic version; an initial eruption of enthusiasm and optimism, hammered down by the relentless seediness of the independent film scene. For one thing, Tetsuo’s hamstrung by his own personality, and tendency to screw things up. His first inclination with Minami is to follow her into the toilets to give her an ‘audition’. And while she’s clearly the better actress, casting her in the movie means screwing over the actors in his workshop, including his previous ‘star’ Kyoko. In this real world, jealousy and bitterness result.

Getting money for a production is no easier, with Tetsuo utterly shifty about how he gets it, although early on we realise that he really ought to be more circumspect. And as he’s a minnow in the moviemaking ocean, he’s prey to the sharks, which have a keen eye for a good script, and a keener eye for talent. He might have hoped to blag a name or two for his movie, but holding onto his cast becomes a challenge. Like the Heather Graham character in Bowfinger, Minami soon learns the value of the casting couch, but the difference here is that it quickly turns her heart black; she adopts the same cynicism as the rest of the industry.

With things so bleak and downbeat, you might wonder what’s to like about Lowlife Love. Well it is deliciously funny, with a rich vein of black comedy running through it. It may have a cynical view of the independent film scene, but with a splendid cast, and a wry eye to the comic potential of its darker moments, Lowlife Love feels like the Trainspotting of the Japanese independent film scene. The pragmatism of Kyoko’s approach to the casting couch is a case in point (she always calls on a friend to check on just how successful a director or producer has recently been before committing). Just like Eiji Uchida’s previous release via Third Window Films, Greatful Dead, Lowlife Love takes a while to click. It’s hard to empathise with any of the characters, especially at first. It’s observed in the film that all directors and producers are lowlifes, but no one in this story comes up whiter than white. But once the film gets going, and you get a sense of its comedic direction, the askew view of its subject, then Lowlife Love really finds a unique and appealing voice. On the strength of Lowlife Love, I can’t wait to see Third Window Films’ next production.

Your Opinions and Comments

Be the first to post a comment!