Review for The Offence

I’ve never seen ‘The Offence’ before now. Indeed, I hadn’t really paid it much heed. The fact that it featured Sean Connery (and filmed just after his last first-phase Bond movie ‘Diamonds are Forever’) meant I’d never really imagined that it would be anything more than a pretty standard tough-guy movie. Which is a shame as it’s way more than that.

1972 was also a year where the dark brilliance of ‘The Offence’ could have been over-shadowed by a glut of now classic film releases including Hitchcock’s ‘Frenzy’, Coppola’s ‘The Godfather’, Bertolucci’s ‘The Last Tango in Paris’and Boorman’s ‘Deliverance’ – all of which delivered an equally darkly cerebral punch in their own way. It could be argued that there was something dark in the air. All the optimisim of the sixties had been replaced by post-Vietnam, post-Watergate cynicism – and a global recession.

‘The Offence’ may be a brilliant film in its way which is not to say it’s either an easy or enjoyable watch. In fact, the affect it had on me was akin to after I’d watched Roeg’s ‘Bad Timing’ a couple of months back. Which is to say, like I’d been dragged through an emotional hedge backwards. Harrowing is an understatement.

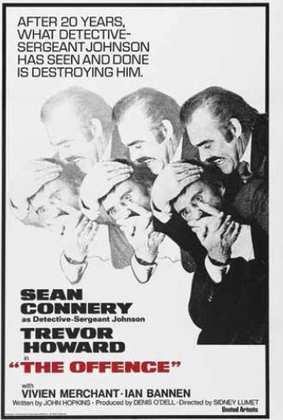

The story goes that Connery was getting tired of his Bond escapades and was ready to throw his toupee to the wind and focus on some serious acting – which he is clearly very capable of. So when he was asked to do one last turn as 007 he negotiated the funding of two further films which would allow him to re-calibrate the public’s view of him and get his career back on track in a new direction. ‘The Offence’ was certainly a new direction. It was the third of five films he went on to make with Lumet including The Hill, The Anderson Tapes, Murder on the Orient Express, and Family Business.

It’s an adaptation of a John Hopkins play (which explains a great deal about the dialogue heavy scenes) which starts out as a fairly grim, almost scandic-noir police procedural.

Imaginatively directed by Sidney Lumet (who uses flashback repeats as well as mute slo-mo with a sparse, cold ambient soundtrack to create atmosphere), it is a highly charged and thought-provoking psychological drama.

Connery plays Detective Sergeant Johnson, a police veteran who is chasing down a serial sex offender who has been abducting and abusing school-children. The pressure has been building for some time and when another young victim is abducted on his watch he is determined to put a stop to it. But to do that he feels as if he needs to get inside the mind of the rapist, to try and get some sense of what drives him and therefore what his next move might be.

When he finds one of the victims, a young school girl, cowering in the undergrowth it nearly drives him over the edge. So when a suspect is brought in for questioning, and refuses to answer questions, he decides to take things into his own hands.

Before long he thinks that the suspect is laughing at him and all the police on the case – goading him and pointing out, when he strikes the suspect, that there is no so much difference between them after all. He recognises a moment of weakness and alarm in Johnson’s face and continues to goad him, suggesting that he gets a vicarious thrill out of re-imagining the crimes. This makes Johnson explode and his violent rebuke ends up killing the suspect. Now Johnson himself is effectively in the dock.

Trevor Howard does a decent turn at being the investigating officer and there is a prolonged scene where, once again, we are forced to the appalling conclusion that, just as there was little difference psychologically between Johnson and the suspect, there is precious little difference between these two men either.

One of the most difficult scenes (and there are many) is Johnson’s with his own wife where we see an abusive, malevolent side which is fuelled by resentment about the way his life has gone. It’s at this point that we start to see that this a man driven to the edge.

It’s a gritty portrayal of a time where the spotlight was beginning to turn on the type of police brutality that was ably reflected in gritty TV dramas like The Sweeney.

Filmed at tiny Twickenham studios for the most part (with bland looking Reading used for exteriors) the sets were built precisely like police stations of the day, but reinforced this tie with breeze blocks to accommodate the violent action which might otherwise have wobbled or destroyed standard sets.

Harrison Birtwistle’s music score (more a selection of disjointed ambient sound-bites) works a treat. In an interview on the disc he tells of how Lumet just left him to it despite the fact that he had little experience writing scores. But the instinctive decision paid off and the results are stunning.

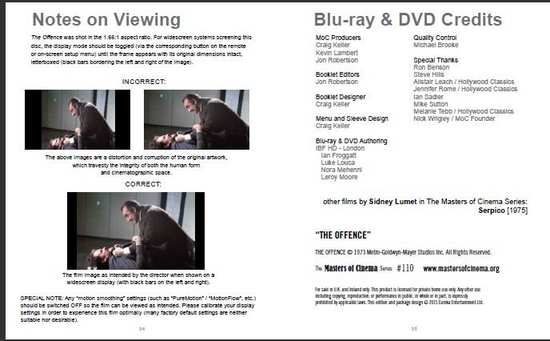

The film looks like it heralds from the UK in the 1970’s. It has dark, flat cinematography and a heavy grain to the film grading. This was tremendously fashionable at the time, adding a gritty realism to film-making; almost the polar opposite to the Technicolor wonder-years.

Extras include an excellent booklet with an essay on the film by Mike Sutton and an archival interview with Lumet. It also features interviews with composer Birtwistle, set designers and the costume lady – all of whom add decent peripheral detail to the making of the film.

A harrowing film but an excellent one, and this version may well be as good as it’s going to get.

Your Opinions and Comments

Be the first to post a comment!