Review of Schindler`s List

Introduction

Charismatic German entrepreneur Oskar Schindler (Liam Neeson), eager to make an easy fortune, moves to Krakow after the Nazi’s invade Poland in order to capitalize on the inexpensive labour available from the Jewish population, now interned in ghettos. Whilst Schindler profits on the back of slave labour, the Nazis steadily increase their progress towards the Final Solution, herding Schindler’s work-force into a labour-camp run by deranged Untersturmfuhrer Amon Goethe (Ralph Fiennes), exposing them, and Schindler, to the deepest horrors of the Holocaust. As the Red Army grow closer to the Eastern front, the residents of the Plaszlow camp are marked for a one-way ticket to Auschwitz, forcing Schindler to make a desperate decision on their fates.

Video

Some dirt and hair-line print damage are evident in places, but it adds rather than detracts from the film’s realist aesthetic. The transfer is very sharp, but exposes some of the limitations of the grainy film-stock (dense whites have a tendency to mist into the sparkling grains of a headache). Also, some of Liam Neeson’s more intricate suit jackets have a habit of segueing into a shimmering monochrome plaid if he turns in the wrong light. In general, not an unqualified success, particularly given the disc change.

Audio

John Williams’ mournful, elegiac score is a little overwrought at times, although it is applied, for the most part, with considerable taste and subtlety. Standard 5.1 has all the bells and whistles one would expect but the DTS track is a welcome addition and certainly lends a lot of body and depth to what is already a typically rich sound design from a Spielberg film.

Features

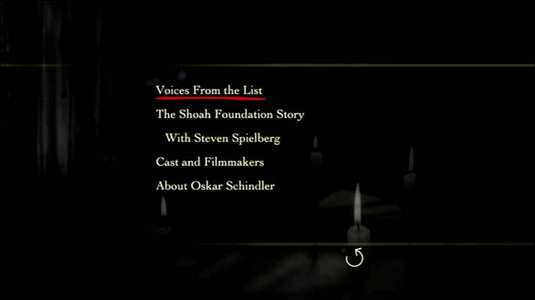

It’s tempting to read something into the collection of extras on this long-awaited collector’s edition, the exclusive dominance of factual documentation emphasizing the film’s status as a historical document over a work of film art. Such deliberate avoidance of any information about the making of the film will likely alienate some of the film’s admirers, and it’s certainly a disappointment for such a highly anticipated title. Annoying, also, is the necessity of the disc change, which occurs after Schindler is arrested for kissing a Jewish girl, just as the film picks up its final harrowing charge towards its conclusion.

At any rate, there’s ‘Voices From the List’, a 70-minute documentary which comprises testimony from many Holocaust survivors, some whose fictional counterparts appear in ‘Schindler’s List’. Despite a rather facile introduction by Spielberg himself, as well as a rather unpolished production around the edges, there are some powerful and moving reminiscences here. A brief bit of text surmises Schindler’s life and there are some pleasingly detailed filmmaker profiles. However, all of this ends up being an extended advertisement for the Spielberg-sponsored ‘Shoah Foundation’, a charity that seeks to re-sensitize new generations about the horrors of racial bigotry through a massive body of eye-witness accounts. Whether or not you find this a worthy cause, (although its methodology does seem a little dubious) you’ll have plenty of time to make up your mind during the 20-minute fluff featurette on the foundation.

Conclusion

With 10 years hindsight from its initial release, ‘Schindler’s List’ seems more and more like the film that tweaked Spielberg’s filmmaking consciousness from block-busting spectacles to a more contemplative model of artistic worthiness. The transference from pap to art worked wonders for him in ‘Saving Private Ryan’, which combined both preoccupations to critical acclaim and massive box office. Subsequent films, such as ‘Minority Report’ and ‘Catch Me If You Can’ have generally suffered from creative diffidence and spiritual fatigue, but ‘Schindler’s List’ still courses with a passion we haven’t seen from Spielberg since ‘Jaws’. It’s peppered with reckless, dynamic touches which helps take the edge off the self-importance: in the opening scene, the silk trail of fumes from a candle cut to the spewing steam of a train, an unobtrusive reference to Kubrick’s bone/space-ship generational jump-cut from ‘2001’.

Time, too, has made the film’s flaws more readily apparent. Whilst ‘Schindler’s List’ sees Spielberg curb his iconographic instincts to some extent, falling back onto documentary filming techiniques with occasionally bracing results, the film never quite manages to avoid Spielberg’s obsession with spectacle. Even the traumatic liquidation of the Krakow ghetto is staged like a set-piece, the same brutally resonant ‘moments’ that turned ‘Saving Private Ryan’ into a grim orgy of flying limbs tearing through shrapnel, albeit framed with a calmer dissonance. As the citizens wait helplessly, the Nazi’s encroaching yells and the clamor of their jack-boots only a few shades away from the synthetic rumbling approach of ILM’s T-Rex. The violence, so coldly deliberate in recreating an objective verisimilitude and its appalled awe, becomes almost abstract with Janusz Kaminski’s grey-scale photography, blood seeping from wounds like oil.

It all adds up to the feeling that ‘Schindler’s List’ is, contrary to popular belief, a deeply expressive work rather than simply a grimly realist one. An expression of old wounds that still ache rather than mere recreation. Kaminski and Spielberg fill the film with rooms shrouded in thick, glinting white mists; depthless, colourless skies and Auschwitz is chillingly, almost surreally recreated beneath a shimmer of fog and searchlights. Shots hop from rattling, you-are-there hand-held cameras to stark, almost painterly tableaus, like the panorama of a dawn Krakow, the windows animated only by intermittent muzzle flashes. Technically and stylistically, the film never quite manages to merge its overwhelming subject and its themes of intentionalistic morality with Spielberg’s typically broadly populist and stylistically unfocused approach.

But what eventually anchors the film dramatically is Steven Zaillian’s lucid, intelligent screenplay. The writing is particularly good on exposing the processes of the Nazi’s systematic program of humiliation, enslavement and genocide. As a result, the clipped, expository first hour is the most absorbing, as Schindler’s Machiavellian charms allow him to grease his way up the Nazi power structure and into his fortune. After the Schindler Jews are imprisoned in Goethe’s camp, it remains compelling, but the narrative becomes curiously episodic – a compilation of oddly disconnected vignettes that add levels of poignancy and even humor. Most surprising, and impressive, is Spielberg’s interest in psychologizing Goethe beyond a mere villainous poise; such as in the extended sequence where, under Schindler’s suggestion, Goethe tries out being a human being and finds that it’s not for him.

Suffice to say, there are a host of excellent performances: Neeson delivers the performance of his life, managing to capture the profound impenetrability of Schindler’s cryptic personality and the emotional paralysis hidden from others and even himself. Ben Kingsley, as ever, vanishes behind his role of Schindler’s Jewish accountant Itzhak Stern, and it’s a credit to his skill that some of the film’s most affecting moments are so potent for being reflected in his dignified composure. Fiennes is mesmerizing as Goethe, a bulbous, insecure human monster who the actor plays as another one of his neurotic loners, reveling in the character’s gnarled frailties and eruptions of volcanic anger. Good too are Embeth Davidtz and Caroline Goodall in underwritten roles as beleaguered woman-folk.

Schindler’s direct motivations are deliberately, and wisely, left largely unexplained (although the re-appearance of the girl with the red coat is implicitly, and rather fatuously, revealed as the dawning realisation of a symbolic motive). Little is made of Schindler’s Catholic upbringing (or the confluence of religious ideals at all), or the moral ambiguity of almost all of his decisions with regard to his Jewish workers. Spielberg, it seems, is able to simplify without even trying. Disappointing too that the film paints the Jews in such diffuse and curiously indifferent terms; despite repeated claims to the contrary, ‘Schindler’s List’ does indeed depict them as somewhat resigned to their fates.

So, whilst ‘Schindler’s List’ feels muddled and even superficial as a document of the Holocaust compared to the likes of Resnais’ remarkable ‘Night and Fog’, Claude Lanzmann’s 9-hour ‘Shoah’ or even Polanski’s recent ‘The Pianist’, as a dramatic work it is amongst Spielberg’s most credible, most satisfying and least mired in arduous sentiment. And in spite of a fatally maudlin conclusion that shows Schindler uncharacteristically breaking down at the feet of his workers, the film remains stimulating both as a corollary to the past, and as a potent reminder of Spielberg’s skills.

Your Opinions and Comments

Be the first to post a comment!