Review of Magdalene Sisters, The

Introduction

A shameful period of Irish religious fascism is given propagandistic treatment by director/actor Peter Mullan. Whilst the story creates a broad panorama of the Magdalene Laundries during the pre-electric washing machine 1960s, Mullan focuses on three central characters to manifest a tripartite demonstration of the evils of coercive religious enslavement. There’s Margaret (Anne-Marie Duff), raped during a wedding; Bernadette (Nora-Jane Noone), busted for harmlessly flirting with adolescent schoolboys; and new mother Rose (Dorothy Duffy), abandoned by her baby’s father and submitted, like their sisters in ‘weaknesses of the flesh’, (young women like Eileen Walsh’s spirited Crispina, and Mary Murray’s docile Una) to the tyranny of Magdalene’s dictatorial nuns. A repressive system of back-breaking labour and slavish religious obedience smothers their spirits, but in its place emerges a few cowering growls of female empowerment.

Video

The grainy 16mm look is effective in bestowing Mullan’s gritty reality, and the transfer replicates this effect surprisingly well.

Audio

Minimalist audio to match the image, nothing special, but efficient enough.

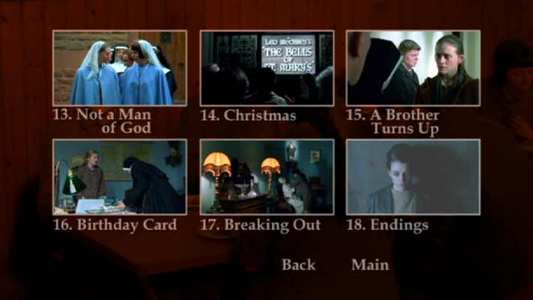

Features

A nice collection of extras here: there is a standard trailer and a descriptive audio track for the visually impaired; Mullan also delivers a fairly reluctant, but nevertheless self-deprecating and detailed commentary, that focuses almost entirely on the technical aspects of the shoot, ignoring the film’s political controversy. The highlights are a series of intense audition tapes featuring the film’s lead actresses, shot on hazily evocative videotape, as well as two of Mullan’s early short films. Firstly, there is the bleak, stark and emotionally draining ‘Fridge’, exhaling a frequently exasperating power but ultimately provides the relief the audience so readily demands. Then there is ‘Close’, a showcase for Mullan’s intense, explosive screen persona, and his claustrophobic visual style. However the film is ultimately little more than its parade of expressionistic shadows and misanthropic housing estate Travis Bickle-isms. Still, both are oddly compelling nonetheless.

Conclusion

To his credit, Mullan manages to construct a compelling saga of cruelty and revolt, and the production design and shooting style possess the haunting clarity of dogmatic minimalism, eerily humming with clandestine Papal authority and a dense spatial emptiness. There are also moments of traditionally ornamental cinematic beauty: Crispina’s suicide attempt is perhaps the most fitting example. So, ‘60s Ireland may be painted in vivid shades of gray, but make no mistake, Mullan’s take on the Magdalene Laundries is a distinctly black and white affair.

Indeed, it would all be a wretchedly worthy trawl if it weren’t for some stunning performances: the feisty Bernadette mutates seamlessly from dotting innocence into Gen-X nihilistic apathy. Similarly, all the other leads deliver performances of such fervent intensity (one might even say Mullan-esque) that the viewer senses a greater depth than is actually delivered. Ultimately, this is a didactic polemic about ritualistic social injustice, and it goes through the motions without blinking an eyelid. Geraldine McEwan delivers a performance barely a whisper away from her memorably demonic appearance as the Sheriff of Nottingham’s mother in ‘Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves’, playing the satanic, calculating, money-hoarding Sister Bridget. Contorting her crooked jowls until they look like a shriveled lemon; she is crisply defined evil, personified in little more than a sculptured caricature.

Religious attitudes are the only things treated with any degree of ambivalence – the girls beg penitently to the Lord to save them from enslavement, scarcely aware that the same superficial devotion is responsible for their detainment in the first place. Mullan gets good mileage out of fleecing the hypocrisy of Catholic morality, climaxing in estranged mother Crispina’s cathartic declaration of “You are not a man of God!” to a fleeing Bishop. What should be a moment of stolen, stilted ecstasy feels more like an attempt to breech into pandering Hollywood liberation. Mullan (along with his first feature, ‘Orphans’) still hasn’t found a way to transmit profoundly moving material to the audience, despite his efficient technique. There’s a sermon on a sheep-field, a single, somewhat Edenic orange for Christmas and a shady, ‘Salo’-esque moment of sadism where the girls naked bodies are paraded and ridiculed by the nuns. The film is full of cruel twists of fate and grimly intimate emotional ‘realities’, all designed to further the film’s simplistic emotional drive. Everything is shot through in gritty tones but nothing resembles the flow of real life, in all its infinitely shaded moral quandaries.

“It’s not subtle, but it makes the point”, is a comment repeated frequently by Mullan on his commentary track, suggesting an awareness of his film’s ham-fisted moral weight. Self-awareness however, as few of us could pretend to ignore by this point, is no excuse, and for Mullan particularly, it becomes the final straw in a movie strangled by its own political simplicity. This one-dimensional tale may be spilling over with undisclosed truth, but the simplistic construction makes for sanctimonious and repetitive drama: Characters are either pillars of vicious, clinical patriarchal piety or quivering, righteously abused victimhood. The audience is permitted no confusion about with whom they are supposed to empathize. As a result, ironically, Mullan’s ostensibly leftist/humanist tract becomes a process of dehumanization for the audience, granted only simplistic, calculated ciphers to identify with. Material of such shocking power and social significance deserves a treatment far more sympathetic to emotional complexity.

In the end, ‘The Magdalene Sisters’ ends up being almost indiscernible from the Hollywood pseudo-liberal whistle-blowing homilies Mullan is trying desperately to avoid. His plastered-on message about human strength, weakness and religious bigotry has all the subtlety and multi-faceted complexity of a pale of cement, not requiring, or even interested, in an audience’s thought process, requesting only their attention, their blind reception. In a way, ‘The Magdalene Sisters’ becomes like the words of bondage prescribed by the Catholic church that indicted its victims to a life of slavery, it requires no conference, no interaction, only obedient attentiveness to its righteous command.

Your Opinions and Comments

Be the first to post a comment!