Mozart: Die Zauberflöte (Böer)

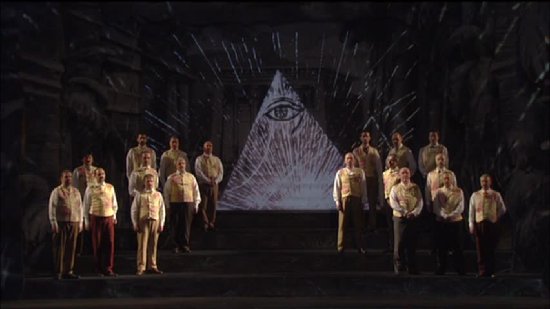

Written in 1791, The Magic Flute is a product of the later years of the European Enlightenment, when philosophical, mathematical and scientific thought was thought by many to be the best way to drag humanity out of the ‘darkness’ of ignorance caused by centuries of hereditary power and faith. Freemasonry was at the heart of the process, yet, most likely because it had no dependency on the church or the aristocracy, was often mistrusted and demonised by those who preferred to be kept in their place and not ask any questions.

Mozart himself became involved with the Masons in Vienna during the last 7 years of his life, and almost inevitably, aspects of Masonic rituals crept into his musical output, not least in this opera itself, although everything we know or surmise about chords, time and key signatures and Egyptian mythology are best read about elsewhere.

This production, by South African artist William Kentridge, focuses on the light/darkness aspect of the Enlightenment philosophy, and despite everything I usually moan about when directors (especially those who are not known for stage works) are let loose on an opera, Kentridge actually gets it!

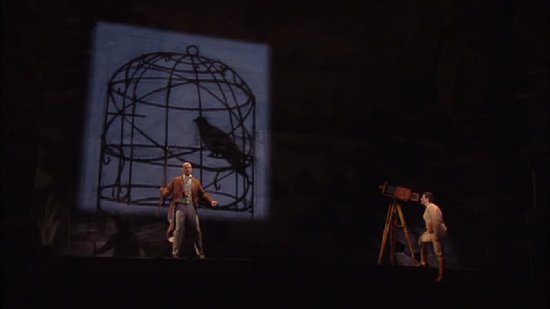

His designs are based on the ideas behind the workings of, or rather, the point of a camera – a utilitarian device that cannot function without light. It also cannot function in pitch blackness and so, straight away, we realise that to get any meaning out of life we need a mixture of light and dark and all shades in between. In a way, we are being told that despite the two main characters’ desire to achieve ‘enlightenment’ by being accepted into Sarastro’s inner sanctum is a fruitless exercise, as their lives will eventually have as little meaning as they did before their fiery and watery trials.

He adds an extra, I’m sure more personal, aspect to the staging by bringing the action forward to late-19th century colonial expansion into Africa. Much of the area was still known as ‘the dark continent’ of course and Kentridge feels there’s a direct link between what the colonialists thought they were bringing the ignorant folk of Africa and their counterparts 100 years previously.

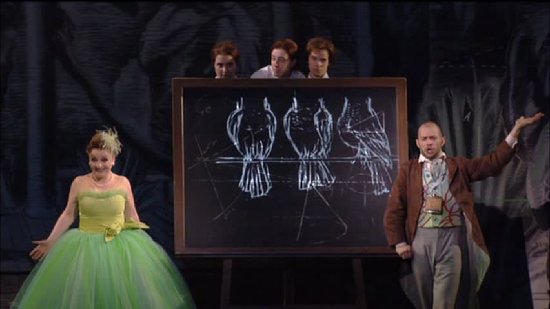

Tamino himself seems to be a hunter. The giant serpent chasing him is brilliantly created by what appears to be a bit of hand shadow play by the three ladies. Throughout the performance, there are projected images of geometric shapes, mathematical problems being worked upon, random images of things going on in the protagonists heads (most notably Papageno’s glass of wine). Birds, animals explosions of what appear to be starry galaxies missed with fireworks are added, and with some clever post-production work, many of the effects are superimposed over the stage, giving us the impression that the whole performance area could be floating around the cosmos (naturally, with an orchestra pit attached).

All these images appear to be chalk drawings, or scratches on rocks, giving the appearance of photographic negatives, matching the charcoal drawing-effect scenery. A ‘contemporary’ tripod film camera is used throughout by various members of the cast, and we see some disturbing historical hunting footage projected at the back, most likely to remind us as to how ‘enlightened’ the colonialists were.

It is all incredibly effective and developed very well indeed for the DVD audience.

And then there’s the music.

I honestly thought there was a problem with the synchronisation at the beginning as the orchestra plays so far behind Roland Böer’s beat it’s amazing they play together at all. Unfortunately, this creates a problem throughout the performance, in that the ensemble really isn’t as tight as you expect from this orchestra. Repeated dotted rhythms often end up as ‘lazy’ triplets and the long, and very difficult accompanied recitative towards the end of Act I is full of scrappy semiquaver-crotchet interjections that makes them sound like one chord. A simple instruction to play notes of the same length in individual sections, let alone the whole band would have worked wonders. But then again, so would playing ‘on’ the beat. Much of the liveliness inherent in the score is therefore lost.

Having said that, Böer’s tempi are very pleasing, and he gets some very effective dynamic contrasts out of the whole ensemble, and there is some particularly beautiful woodwind playing. The quick shot of the keyed glockenspiel in the pit is great fun, mainly because it shows how hard you have to hit the keys just to get a sound out.

And then there’s the extra music.

Obviously not satisfied with what Mozart actually wrote, we have what seem to be improvised passages on the keyboard during more ‘thoughtful’ passages on stage. Are they trying to install background music as if it were a film? Not content with that, I’m sure there were an extra three orchestra chords in one the temple scenes, and why Tamino plays something more akin to Poulenc when remaining’ silent’ in front of Pamina is anyone’s guess.

This is obviously a result of what is mentioned in the final short paragraph before the synopsis in the accompanying booklet:

”Musically too this new performance blurs the opera’s line between speech and song with its use of some of René Jacob’s performing notes”

There is no further clarification of what precisely these are, and so I had to do some searching myself. This is a link to a Guardian article about Jacobs’ own recording of the work.

Make of it what you will. To be honest, I think it is an assumption too far if we are all expected to know what these particular ‘performing notes’ are, and even Böer, in his (sing)spiel for the extras doesn’t mention them at all. Missed chance.

On stage, in amongst the graphical storm, things are generally very much more satisfactory.

Saimir Pirgu (Tamino) has one of the most consistently fine voices I’ve come across in this role, although facial expressions that should reflect terror or love tend to be the same. He is definitely able to ‘stand and deliver’ very well though, and the duets with Genia Kühmeier (Pamina) are very beautiful.

Kühmeier herself is far more relaxed, as her stage presence proves, and ‘Ach, ich fühl's’ is a fine exercise in control, despite the unsure start from the strings. A couple of very strange fade-outs during this aria made me suspect that it was actually a very clever way of using footage from a couple of performances…or, it could have been another deep and meaningful example of the need for both lightness and darkness. We shall never know.

Sarastro is probably one of the more serious of characters in opera and has music to match. Günther Groissböck does a fine job in carrying across the gravitas required, although it feels as if his voice doesn’t quite match the whole range required for the role. Nevertheless, there are far less satisfactory Sarastros out there.

Albina Shagimuratova’s Queen of the Night is rather vocally fantastic, with a few issues hitting the lower notes of some of arpeggios, yet facially is almost completely static and so the underlying evil of the character doesn’t come through at all.

Alex Exposito as Papageno seems to the only person on stage who has come to life. His ability to sing as if it’s actually fun to do so carry much of the performance, and successfully manages to raise a couple of titters from what appears to be a very dour Italian audience. He also manages to play his own pipes (nicely set up as part of his hip flask) without trouble, something I’ve seen go horribly wrong on occasions.

Disappointingly, Peter Bronder tends to shout out many of his notes, losing much of the music altogether to get over the character of this nasty little man, so I suppose we should give him full marks for trying.

The extras on the disc consist of short talks (12 minutes in all) by director and conductor.

Kentridge expands very nicely on his ideas before the production, and Böer demonstrates then ‘threesomes’ involved in this work, from the key signature of the overture, through the repeasted chors and the number of ladies and ‘boys’ (sung here by sopranos). Nothing particularly new is learned, and there is absolutely no mention of René Jacobs, which is a shame.

The chorus is small, but pack a real punch when it’s needed, so no complaints there.

Sound and vision is exemplary, and even more so with the post-production effects which I mentioned earlier.

Overall, this is an excellent DVD, which deserves to be seen for William Kentridge’s fascinating take on the popular story and some wonderful singing. If you are not too fussed about orchestral detail, then it comes highly recommended.

Your Opinions and Comments

Be the first to post a comment!